Posts Tagged ‘“VCI Entertainment”’

Now we’re those old film guys…

My first encounter with Robert L. Lippert was in 2004, after I’d called and asked him if he’d be willing to be interviewed about his legendary father, producer-distributor-exhibitor, Robert L. Lippert, Sr. This was shortly after I purchased the 100+ feature film library produced and distributed by “Senior,” as Bob called him.

Bob lived in Pebble Beach, California, with his lovely wife Hong Sook. Their house was filled with world-class Asian antiques, and his living room walls lined with photographs of him and his many adventures…and he had a lot of adventures; as a film editor, producer, exhibitor, aviator, restaurateur, and I’m sure others he didn’t have the wall space to document.

Bob took me to breakfast and we talked about his father, then we went over to his stately home. He led me downstairs to his office which was filled with posters from movies he had worked on, “High Noon,” “The Tall Texan,” “The Sins of Jezebel,” and many others. Soon the subject of conversation turned to Bob himself. He had a lot to say, and did so with gruff, colorful language that you’d expect of a veteran of B-movie making. No one had ever asked him about his life in the movies for 50 years, and he was delighted to have someone interested, especially an avid listener like me.

We met several more times, most notably when he invited my wife, Donna, and I for lunch at the Pebble Beach Country Club. I dressed nicely with a sport jacket, but wore jeans which I found out was taboo at the country club. He took me back to his house and gave put on a pair of his slacks. I was a size 32, and he was a shorter man who wore size 38. I was quite a sight, but I didn’t care.

Bob’s passing saddened me because he was my last link to the “old school” filmmakers I so loved.

My good friend, Steve Durbin, recently told me, “Remember those old film guys we loved to hear stories from?”…“Now we’re those old film guys.”

Robert L. Lippert, Jr. Filmography:

Massacre (1956) Producer

The Black Pirates (1954) Co-producer

The Big Chase (1954) Producer *

Fangs of the Wild (1954) Producer

Sins of Jezebel (1953) Producer

The Great Jesse James Raid (1953) Producer

Bandit Island (3-D short) Producer, director *

The Tall Texan (1953) Assistant film editor

Hellgate (1952) Assistant film editor

The Jungle (1952) Assistant film editor

High Noon (1952) Assistant film editor

FBI Girl (1952) Assistant film editor

Pier 23 (1951) Assistant film editor

Roaring City (1951) Assistant film editor

The Danger Zone (1951) Assistant film editor

The Steel Helmet (1951) Assistant film editor

The Bandit Queen (1951) Assistant film editor

All except “The Black Pirates” and “Bandit Island” are available on DVD.

* “Bandit Island” was later incorporated into “The Big Chase.”

These passages appeared in a previous a previous post, “The Lippert-Fox Productions/Lippert Trivia”:

“’The Black Pirates’ (1954) was shit, and ‘Massacre’ was no good either.” — Producer, Robert L. Lippert,

After a day of filming “Massacre” (1956) in Guatemala Producer Robert L. Lippert, Jr. was relaxing in his hotel room and heard gun shots in the room next to him. Recalling that a General was staying there, he immediately calculated it was an assassination (it was.) Lippert didn’t want to be shot as an eye witness, so he jumped out the window and ran on foot all the way to Mexico, and the cast and crew, who were staying in another hotel, departed by plane.

Again during the filming of “Massacre,” Lippert, Jr. said he was on location in a rural town where he found the electrical power was at best unreliable. Of course power was essential. To proceed with filming he went to the local airport, such as it was, which was powered by a generator. He paid off government officials to obtain the airport generator during the daytime hours. Daytime air operations ceased, and each night the generator was returned to the airport thus enabling planes to once again take off and land.

There wasn’t enough money in the production budget to afford a pirate ship in “The Black Pirates” (1954), so the movie begins with the “pirates” arriving on shore in a row boat. They never leave land for the entire movie.

Visit our website to order DVDs from the Kit Parker Films Collection –

Keep up to date with our new Sprocket Vault releases by liking us on Facebook www.facebook.com/sprocketvault/

Also, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel:

Four Guys from Oakland Part 1

Posted on: October 6, 2011

“Watch Horror Films – Keep America Strong” – Bob Wilkins

KTVU, Channel 2 in Oakland, California, was one of the nation’s powerhouse independent television stations. I started watching in the late 1950s/early 1960s when they aired cool (to a kid) live shows such as Captain Satellite, Roller Derby, and National All-Star Wrestling. But movies were consistently their ratings grabbers. In 1986 KTVU became part of the Fox Network and, of course, its programming forever changed.

KTVU fixtures I was happy to have met…

BOB WILKINS

“Don’t stay up late, it’s not worth it”

From 1971 to 1979, Bob Wilkins, the cigar-chomping, dead-pan humored, host of Channel 2’s “Creature Features,” whose deprecating comments about his program’s library of grade B and Z horror and science fiction films were irresistible. (He did show some good movies, too). One of his hallmarks was to recommend that his viewers not watch his movie, but change to another channel. He even read the TV Guide listings of opposing programs! Sponsors were ticked off until they found out that his gimmick jacked up ratings. I, for one, found his approach irresistible, although one viewing of “Creature from the Haunted Sea” was enough.

“This movie has two things going for it…it’s in color and they speak the English language.”

Bob interviewed big-time horror and sci-fi icons like William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, Ray Harryhausen and Christopher Lee. I first time I met Bob in 1972 when he invited me to be a guest on his show. Thank god he put me at ease with his low-key bedside manner as I’d never been on television before, much less a show with so many viewers. He must have liked me because he had me as a guest several times, and I was always grateful for the plugs. 1979 Bob called it quits at KTVU, although he continued with his Sacramento “Creature Features” show on KCRA a few more years. Bob was a very funny guy, with a wonderful, wry sense of humor, and that voice…I can still hear him say…

“Well, that’s it. I told you it’s bad!”

BOB SHAW

Bob Shaw was one of the nicest, most knowledgeable, and unpretentious film critics I’ve ever met. Before he was hired by KTVU, he was already working gratis behind the scenes at “Creature Features,” providing Bob Wilkins with trivia for the show. In 1977 Bob W. talked Channel 2’s film director, Jim Skinner, into hiring Bob Shaw as a film editor. Later Bob Shaw became the station’s film critic, and he was one of the best. The stars he interviewed invariably liked (some adored) him, and that interviewer-interviewee connection made his movie critiques that much better.

Bob and I met in the early 1970s while I was a guest on “Creature Features.” We both were 16mm film buffs, so spoke the same language, but we didn’t have much time to talk because he was nervously running around the set making sure props were in order. We spoke on the phone a few times through the later 1970s, but I didn’t see him again until the early 1980s when he had been working as a film editor. KTVU ran lots of movies, so he was in movie buff heaven. When the station first let him review a new movie on-camera, he was not too sure of himself, as anyone in the same situation would be, but it was clear from the very beginning he was going to be one of the best. And he was.

We lost both Bob Wilkins and Bob Shaw in 2009.

Visit our website to order DVDs from the Kit Parker Films Collection –

Keep up to date with our new Sprocket Vault releases by liking us on Facebook www.facebook.com/sprocketvault/

Also, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCLHjjG-o5Ny5BDykgVBzdrQ .

Kit Parker Films @40 (Part 2)

Posted on: September 20, 2011

It all started in 1971.

Before and during my stint In the Navy I read every 16mm rental catalogs…cover to cover…dozens of times; I knew that was the business I wanted to be in. Fortunately, I was able to write the copy and do the typesetting of my first 16mm rental catalog on board ship before being released from active duty in June of 1971. on Back home my father, Al Parker, drew the illustrations, and continued doing so until his death in 1985.

I wanted to stay in broadcasting until my film library took hold. Using the G.I. bill, I earned my First Class Radio Telephone License from the FCC. It was very difficult to obtain, but I knew it would open a lot of doors because a “First Phone,” as they called it in broadcast, would allow me to be the engineer in charge of a television or radio station. Disc jockeys needed that license in those days, and I had successfully did that in the Navy.

There was a law back then that employers had to hire back returning vets for a minimum of 30 days, so with my new license I returned my previous job at KSBW TV. I printed and mailed out my first catalog a month later. Despite the protestations of the Chief Engineer, Willis Wells, my employer let me go after the obligatory 30 days. They had too many Technical Directors. My original television mentor, Dwight Wheeler, and Chief Engineer (Earle…wish I could recall his last name) were gone; and my timing, essential for a technical director, had declined just enough during my two years service on the aircraft carrier. My old job just wasn’t as fun any more.

It turned out I wasted my time studying for the test because the day my catalogs were received by potential customers, the orders pouring in! A problem I was happy to have.

In those days 16mm distribution was a good-sized industry. Every organization, institution, school, church, and so on, which now use DVD’s, satellite or cable for entertainment, used 16mm film. Although some distributors offered classics and foreign films, by far the majority of movies were rented for entertainment. Those in the industry called it “general entertainment” or “institutional users” which really meant babysitting for all ages. The majority of those audiences didn’t care about splices and scratches on the film, nor did the distributors, especially since prints were expensive.

At the same time my target customer: colleges, universities, high schools, and other organizations, had film study classes. They were tired of paying good money for poor copies. Low overhead allowed me to offer quality prints and low rates…an appealing combination to the many users of 16mm films.

My first films were all in the public domain because I couldn’t afford to pay major studios for movies like the other companies I admired, such as Budget Films, Films Inc., United Films, and Westcoast Films. Al Drebin owned Budget, and David Arnaud’s company was Westcoast, and they became mentors. Later on Willard W. Morrison of Audio Brandon and George Crittenden of Films, Inc. joined them as cheer leaders for the new kid on the block.

A year or two after opening my business I acquired my first copyrighted movies, and it was a big thrill. Bill Blair, a real good guy, of United Films, licensed several 1950s RKO Radio features to me. They were only B+ to A- productions, but even lesser works by greats like Fritz Lang, Samuel Fuller and Nicholas Ray were a coup. (Incidentally, United Films became VCI Entertainment, my current DVD distributor. This gave me pleasure of working with the same people as film morphed into digital…almost 40 years later.

My next acquisitions were movies distributed theatrically by the Walter Reade company, made up primarily of British titles from J. Arthur Rank. A few good ones, but most, like Tawny Pipit (!) weren’t of much interest outside of England.

Not long after, Marty Pincus, a salesman from Learning Corp. of America, mystified that I could run an operation such as KPF out of a rambling country house. My first house burned three days after I moved in, and that was a close call for Kit Parker Films. Marty sold me some first-rate British classics like Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet. He also represented a series of movies produced independently by Walter Wanger, of which Stagecoach was a big-big seller. I could afford all of these movies because LCA financed the deal. Kit Parker Films always operated on the cash it generated, not bank loans. (In those days we paid a flat fee to the producers and it allowed us to rent the films as much as we could. Later on, unfortunately, the producers got 50% of the money derived from each booking.)

The next studio to give me terms was Columbia Pictures. Their salesman was Dennis Doph, a film buff, smart and a real character, who always made a big effort to give me as many movies as possible, and affordable. Columbia had a terrific library, with big sellers like On the Waterfront and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. We continued to acquire Columbia titles for years thereafter. One of the most satisfying parts was making the silent-era Frank Capra films available for the first time. (The negatives came from Sweden and I had them translated.)

(Acquisition of the National Telefilm Associates (NTA) library, later known as Republic Pictures, opened doors for me and will be discussed in the next blog.)

Chuck Cromer was the first non-theatrical salesman I met at Disney, and his boss, and later my contact, Linda Palmer, made the decisions. I always felt like an interloper at Disney, but she gave me good movies. Unfortunately there were so many restrictions, probably not all her doing, I never had a lot of success with that library.

In the late 1970s, and especially early 80s, I saw that VHS was quickly making inroads on 16mm. The quality was not good, but film library budgets had been cut across the board, and most customers could only afford video. The “general entertainment” film libraries were the first to fall because they, and their customers, didn’t care much about picture and sound quality.

Lots more in the next blog.

Visit our website to order DVDs from the Kit Parker Films Collection –

Keep up to date with our new Sprocket Vault releases by liking us on Facebook www.facebook.com/sprocketvault/

Also, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel:

Kit Parker Films @40 (Part 1)

Posted on: August 18, 2011

My fascination with films began with the Pincushion Man.

When I was young, everyone watched movies in the theatre or on television. That’s it…no DVD, Cable TV, Satellite, and YouTube; in fact, no digital anything. Home movie enthusiasts watched home movies on 8mm (16mm if they were lucky) and that’s about it. Then, as now, there was a big demand for movies at educational institutions, and all kinds of organizations and institutions. That need was fulfilled by 16mm film, and distribution of them was a good sized business from the 1920’s to the late 1970s. A portable 16mm projector, screen and, of course, a film was all that was required. It was a hassle, but that’s how it was done. The AV guys who ran the projectors had the same appearance and personality of computer nerds today. Film buffs remember them, but most young people won’t know what I’m talking about,

8mm was the primary format used for home movies, and my father shot a lot of them. To augment family films he showed ten minute silent versions of sound movies, mostly cartoons, which were sold in photo shops under the Castle Films label. One was The Pincushion Man, a re-title of Balloon Land (Ub Iwerks, 1935); it mesmerized me with its bizarre characters and surreal color (Cinecolor, a two color process). Dad had two others, Little Black Sambo and Sinbad the Sailor, also 1935 Cinecolor cartoons from Ub Iwerks, but to me there was Pincushion Man and then all others.

That was the origin of my interest in films. The next year I went to the movies and saw a feature film compilation of silent comedies, Robert Youngson’s The Golden Age of Comedy (1957). It was, and is, terrific. (I can’t believe it still isn’t out on DVD.) [*]

Soon after, I began collecting my own Castle Films, “dirty dupes” from Home Movie Wonderland, and eventually switching to Blackhawk Films. Blackhawk was the best; silent comedies, and the be-all-end-all of comedy, Laurel and Hardy. Then I got interested in the physical prints as well as content. My first Kit Parker Films “catalog” (three pages) offered 8mm movies for sale. I think I was 11, and my inventory came from offbeat mail order catalogs. At 13, I began borrowing 16mm public relations films produced by oil companies, railroads, and other corporations which offered them free to organizations through a distributor called Modern Talking Picture Service. They had film exchanges throughout the country, and offered countless numbers of films on the behalf of a corporate clients. By and large, they were well produced and entertaining. I told Modern there were several resorts where I lived that were interested in showing those types of films. The sources of entertainment were very, very limited in those days in semi-rural areas like Carmel Valley, California, where I grew up. Modern, who was paid by the sponsors every time a film was shown, asked me if I would sub-distribute for them. My folks took me to their San Francisco office, and when they saw me, they were stunned and amused by my age. They looked at each other wondering what they got themselves into. I got the films, though!

At 14 I started a weekly kiddie matinee at the local community center which showed a feature, short subjects and sometimes a serial, every Saturday at the local community center. Tickets sold for $.35 and it was a big success. Over the next four years, I ordered the films (the best part), ran the projector and bought the candy. The profits went to maintenance of the building.

By 14 my collecting was 100% 16mm…I bought and sold prints. As my collecting continued I also began shooting my own movies with a Bolex camera my folks gave me one Christmas. Although I never really had an interest in shooting movies, the news anchor, Mike Morisoli, at KSBW-TV (stood for “Salad Bowl of the World”!) in Salinas, California, had faith in me and provided unexposed film to cover events such as rodeos and car racing. Back then news stories were all filmed, and my footage ended up on the 6 O’clock News…way cool for a 16-year-old.

At 18, KSBW Program Director, Dwight Wheeler, hired me as the weekend film editor. In those days television broadcast only network shows, live programming (mostly the News) and lots and lots of film…no video tape. There were racks and racks of TV shows at the station, and even more feature films! At one time or another they had, MGM, Columbia, Universal, Warner Bros. and United Artists. The best distributor was NTA…they had 20th Century-Fox and Republic Pictures. Syndicated TV shows ranged from Sergeant Preston of the Yukon to Gilligan’s Island.

My job was to assemble the filmed programs and add the commercials. I had to find the best spots to insert commercials into feature films, and sometimes editing them down to fit into specific time slots. Everything had to be timed right down to the second. I learned fast because of my film experience, so soon after had lots of spare time which allowed me to study how the technical directors worked. A “TD,” as they were known, sat at a large console full of switches and buttons, like you’d see today at a recording studio. They pushed the buttons and moved levers at the correct time to assure everything went on the air at precisely the right moment. Today only live programming still uses a TD; everything else has long been computerized. During half-hour news program there could easily be scores of decisions and manipulations; most had to be anticipated five seconds ahead of the actual event. On the weekends when only the TD and I were at the station, they would teach me how to do the job. I was a fast learner and had quick reflexes, at least in those days! When one of the TD’s quit, the others recommended to the Chief Engineer that I take his place, and I went from the film room to the control room. I became akin to a super projectionist…and had a ball. A few months later I was the TD in charge of all of the prime time programming.

1967 the Viet Nam war was raging, and young men were being readily drafted. I didn’t want to end up in a jungle shooting people, so joined the Navy Reserve, and ended up on the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise. It was a small city with over 5,000 officers and men. Logically, they put me in charge of the ship’s entertainment television and radio stations; illogically they moved me into the Public Affairs Office for the duration where I worked on the daily newspaper, gave tours of the ship, and mostly shuffled papers. Morale on the ship was poor; I think our Captain idolized Captain Bligh, and my Chief Petty Officer was never happy because flogging was outlawed.

Fortunately I had enough free time to work on creating my passion, Kit Parker Films.

OF PART ONE

[*] Not to be confused with other productions on DVD with the same name.

Cool book about Castle Films:

———————-

Visit our website to order DVDs from the Kit Parker Films Collection –

Keep up to date with our new Sprocket Vault releases by liking us on Facebook www.facebook.com/sprocketvault/

Also, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel:

Sorry, I do not profess to be an expert on copyright law! But those interested in the intricacies of it may find the below of interest.

Fifty years ago producer Adrian Weiss commissioned an opinion from renowned copyright and trademark attorney, E. Fulton Brylawski, principally regarding what constitutes “publication” in copyright law. The following is a slight abridgement of the letter, the original of which I donated to the Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences:

Mr. Brylawski opines:

In the case of Jewelers Mercantile Agency v. Jewelers Publishing Company, decided by a New York state court (1892) it was held that the leasing of copies of a book to subscribers was a publication, even though the lessor never parted with the title to the work and the lessee agreed to return the copy after the expiration of the term for which it had been leased.

Motion pictures are almost never sold or placed on sale and it is doubtful that they are “publicly distributed,” but it is generally believed that the leasing of prints of motion pictures to exhibitors for theatrical showing, constitutes a publication of the pictures under the decision referred to, but the question has never been squarely decided that motion pictures are actually published by this method of distribution. [Keep in mine that this letter was written before the advent of home video]

While I feel that there can be no real doubt on this point, it does not necessarily follow that because a motion picture may be in the public domain, anyone may freely copy and exhibit or distribute copies of the film.”

Anyone who may have lawfully acquired title to any print of the pictures, may use same in any manner he chooses, but a person who obtains temporary possession of any property for one purpose and who converts same to his own use by using it for a different purpose than that for which possession had been temporarily parted with, can be restrained and would be liable to damages for the conversion.

In view of the fact that no one, other than yourselves, has any prints or negatives of these pictures [The “Chuckleheads” TV series]*, there cold be no danger of competition from outside sources.” Perhaps my reference to one being in “lawful possession” of a print of one of your old pictures was ambiguous.

If one had a print which had been sold, the purchaser would have lawful possession. If a laboratory had liens on prints and they were sold to satisfy the liens, the purchaser at such a sole would have lawful possession. [Could make copies if the film is in the public domain.]

If a print was parted with for screening purposes or for exhibition or telecasting, the possession of such a print would be a lawful one, but the making of a copy would be an unlawful use, for which the offender would be liable.”

The exhibition of the picture is not a publication and an unpublished motion picture may be freely exhibited without changing its status as an unpublished work. If the picture was not published, it is unimportant whether or not it had a notice of copyright, as this notice is only required in the case of published works.

Publication of a motion picture occurs when copies are sold or leased to theatres for the purpose of exhibition. It is the leasing which constituted publication – not the exhibitions of the film.

The copyright law does not define what constitutes publication. It merely states that the date of publication shall be the earliest date when copies were placed on sale, sold or publicly distributed. The production of a play on the stage is not a publication of the play and exhibitions of motion pictures on the screens is similarly not a publication of the pictures.

[*] “Chuckleheads” is a series of 150 five-minute shorts edited from Weiss Bros. Artclass Pictures comedies, with added music and sound effects

Visit our website to order DVDs from the Kit Parker Films Collection –

Keep up to date with our new Sprocket Vault releases by liking us on Facebook www.facebook.com/sprocketvault/

Also, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel:

A Hammer Film or not?

Film historian Sam Sherman nails it….

(A series of emails between film historians Sam Sherman and Rick Mitchell as prompted by my blog)

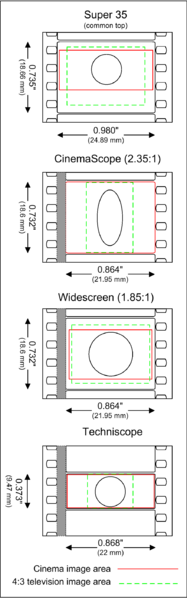

RICK MITCHELL: …but all Regal [“B” movies produced by Robert L. Lippert and released by 20th Century-Fox] films I’ve seen after that were credited in being in RegalScope, including British made THE ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN OF THE HIMALAYAS, which was actually shot in what’s now called Super 35; [a film collector] e-mailed me that his 35mm print credits Megascope, the term Hammer used for the films it shot in Super 35 and Columbia used on spherical films it released in Europe with anamorphic prints.

SAM SHERMAN: There is so much information and especially mis-information on this title due to several reasons – The claims that this is a Hammer film or a Regal film are completely Wrong. The film was originally made as a US British co-production between (US) Buzz Productions Inc. (Bob Lippert, Bill PIzor, Irwin Pizor) [**] and (UK) Clarion Films Ltd. (Jimmy Carreras) (a separate company and not legally part of Hammer) with Fox handling all world-wide distribution outside of the Clarion territories of UK and Japan, as the film was a UK quota financed film there, as released by Warners. The process listed was somewhere “Hammerscope” elsewhere “RegalScope”, but was most likely regular Cinemascope.

In the Fox territories the film was cut by several minutes and re-titled ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN OF THE HIMALAYAS. Videos here are from the British master and show the Warners logo and UK credits. The US Theatrical release was the top of a double bill with GHOST DIVER, which I think is a Regal film…, as second feature. US TV was originally handled by Seven Arts (which had a Fox TV film group package) and later became part of Warners. I have a Seven Arts 16MM TV print with different (US) credits which had a prominent credit for Buzz Productions, rarely seen elsewhere. My company (IIP) [Independent International Pictures] is the owner of the Buzz Productions interests. This is probably the best film that the Clarion and Hammer production team ever made. It is finally getting a reputation, is shown yearly at a special film festival at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood and fans finally have gotten to appreciate it. When I took over the rights to this film and started working with Fox they thought nothing of the film until I told them it was great! They didn’t believe in it as they had mis-handled it originally and it made no money. Once, due to my efforts, they reviewed all of these issues and they started marketing it to Cable TV in the US (including HBO) where they did a great deal of business. This film was in the Red from 1957 to the 1990s until I took it over and now, it is solidly in the black.

In the Fox territories the film was cut by several minutes and re-titled ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN OF THE HIMALAYAS. Videos here are from the British master and show the Warners logo and UK credits. The US Theatrical release was the top of a double bill with GHOST DIVER, which I think is a Regal film…, as second feature. US TV was originally handled by Seven Arts (which had a Fox TV film group package) and later became part of Warners. I have a Seven Arts 16MM TV print with different (US) credits which had a prominent credit for Buzz Productions, rarely seen elsewhere. My company (IIP) [Independent International Pictures] is the owner of the Buzz Productions interests. This is probably the best film that the Clarion and Hammer production team ever made. It is finally getting a reputation, is shown yearly at a special film festival at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood and fans finally have gotten to appreciate it. When I took over the rights to this film and started working with Fox they thought nothing of the film until I told them it was great! They didn’t believe in it as they had mis-handled it originally and it made no money. Once, due to my efforts, they reviewed all of these issues and they started marketing it to Cable TV in the US (including HBO) where they did a great deal of business. This film was in the Red from 1957 to the 1990s until I took it over and now, it is solidly in the black.

RICK: Kit Parker forwarded to me your comments about the rights history of this film, which sound very complicated because it was an international co-production. ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN was shot by the technique known today as Super 35: full aperture spherical photography composed for 2.35, which would be extracted and squeezed to a dupe negative for release printing. This was originally done as Superscope but didn’t work as well on color films as with black-and-white and we are now discovering that a number of black-and-white films from the late Fifties released with anamorphic prints and advertised as being in CinemaScope or similar “Scopes” were actually shot that way. Megascope was Hammer’s term for films shot this way and Columbia used it on some films shot and released spherically in the US but with anamorphic prints in Europe, including THE 7TH VOYAGE OF SINBAD [1958]!

SAM: I won’t believe this super-35 story on ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN until I see a piece of film in my hand like that. I  remember seeing some Superscope films in theatres (Tushinsky process) originally… especially INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS [1956]. It was inferior looking and very grainy from blowing up that negative. ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN always looks very good leading me to believe it was shot with an anamorphic lens and not blown up from part of a negative. I worked on two films shot in Techniscope (a similar idea using half the negative) and squeezed into an anamorphic version – and it usually looked grainy and horrible. If SNOWMAN was shot the same way, it should look equally bad which it does not.

remember seeing some Superscope films in theatres (Tushinsky process) originally… especially INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS [1956]. It was inferior looking and very grainy from blowing up that negative. ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN always looks very good leading me to believe it was shot with an anamorphic lens and not blown up from part of a negative. I worked on two films shot in Techniscope (a similar idea using half the negative) and squeezed into an anamorphic version – and it usually looked grainy and horrible. If SNOWMAN was shot the same way, it should look equally bad which it does not.

Unfortunately, we have not had access to MGM’s files to get their side of this, only Panavision’s. Obviously, they couldn’t publicly announce it as it would have been in violation of their licensing agreement with Fox. One giveaway is there is a credit on these films saying “Process lenses by Panavision”, which was used when Panavision optical printer lenses were used for conversions. Through 1960, films shot with Panavision lenses, though credited as being in CinemaScope, carried a sub credit “Photographic lenses by Panavision. Unfortunately, this credit appears near the end of the main title sequence on the card with the copyright notice, etc., so you have to watch the film’s main title sequence to catch it. One other thing I noted was that the films’ original negatives were cut into A&B rolls so they wouldn’t have to go to another dupe stage for dissolves and fades, just title sequences and opticals. We’re fairly certain all their black-and-white “CinemaScope” pictures released in 1957 and 58 were done this way, but still need to research the 1959-60 releases because MGM had begun using Panavision lenses on its color films about that time. Marty has confirmed that THE GAZEBO, released at the end of 1959, was shot anamorphic.

[**] The name “Buzz” probably came from Robert L. Lippert, who had just produced “The Fly” (1958).

Sam Sherman, writer, producer, distributor, and film historian:

http://www.badmovieplanet.com/unknownmovies/reviews/independentinternational.html

Rick Mitchell, film editor and film historian.

http://www.in70mm.com/news/2007/rick_mitchell/index.htm

Wide Screen 101:

http://www.cinematographers.nl/FORMATS3.html

http://www.widescreenmuseum.com/

———————

Visit our website to order DVDs from the Kit Parker Films Collection –

Keep up to date with our new Sprocket Vault releases by liking us on Facebook www.facebook.com/sprocketvault/

Also, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel:

Lippert Filmography: Responses

Posted on: July 19, 2011

Ronnie James, one of the great unsung movie and television researchers felt that the Filmography would be more useful and telling, if it was in chronological order. It started out that way, but I found too much conflicting information among my various research publications…but he’s right…it should be.

Film editor and film historian Rick Mitchell has great credentials when it comes to wide screen cinematography. He asked several excellent questions that I’m sure others have wondered about as well.

RICK MITCHELL: I believe there are some errors in the Lippert piece. I don’t believe Sam Fuller’s CHINA GATE and FORTY GUNS were made for Lippert but under a separate deal Fuller’s Globe Productions made with Fox, like Edward L. Alperson’s. THE FLY is not considered a Lippert production but an official Fox one.

THE FLY is definitely a Lippert production. Director Kurt Neumann came to Bob Lippert with the story, and Lippert felt it would be a big hit so, according to Dexter, authorized a $700 – $750K budget…astronomical for a Lippert production, but small by Fox standards. Most of the money went into special effects and, of course, it was filmed (in Canada) in color. Lippert showed it to Fox president, Spyros Skouras, and he decided to make it a Fox “A” release.

KIT: Sam Fuller was the producer of both CHINA GATE and FORTY GUNS, released in 1957.

These were Lippert RegalScope productions that so impressed the Fox brass that they were released as Fox/CinemaScope pictures. Head of production was Bill Magianetti, and his assistant was Maury Dexter. I spoke to Dexter and he confirmed this and also went into detail about the filming. Maury also told me some great Fuller stories connected with those two pictures which I’ll reveal in a future blog!

These were Lippert RegalScope productions that so impressed the Fox brass that they were released as Fox/CinemaScope pictures. Head of production was Bill Magianetti, and his assistant was Maury Dexter. I spoke to Dexter and he confirmed this and also went into detail about the filming. Maury also told me some great Fuller stories connected with those two pictures which I’ll reveal in a future blog!

RICK: Are you sure THE FLY was filmed in Canada? I’d seen THE GIFT OF LOVE a few weeks before I first saw THE FLY and was shocked to see the same interiors of the house in both films. Fox did recycle standing sets: the schoolroom build for PEYTON PLACE appears in THE YOUNG LIONS and THE LONG HOT SUMMER with no changes, for example.

KIT: Rick was mostly right…only some scenes were filmed in Montreal, the rest at Fox studios.

In one of my blogs I wrote that Lippert couldn’t put his name on any of his Fox productions because he totally alienated the unions by insisting on releasing his earlier productions to television and refusing to pay residuals.

RICK: Lippert takes executive producer credit on THE YELLOW CANARY (1963).

KIT: Yes, by 1963 the union problems were behind him.

RICK: The first Regal film credited on the film as being in CinemaScope; I haven’t seen any ads or trailers, so I don’t know what’s on them.

KIT: I do know they used CinemaScope lenses on all of the Regal’s, but Fox didn’t want to use that name on low budget, black and white second features. One thing that continues to stump me is some of the Regal prints have the Fox logo, and other prints of the same picture say Regal Films! Maury Dexter didn’t know, either, so it is a probably a question that will never be answered.

RICK: See attached frame blowup from a friend’s 16mm print of STAGECOACH TO FURY; I now have one of my own. It has the Regal Films logo at the head. I have not seen any of the other RegalScope films released in 1956 and don’t know how they were credited but all Regal films I’ve seen after that were credited in being in RegalScope, including British made THE ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN OF THE HIMALAYAS, which was actually shot in what’s now called Super 35; [a film collector] e-mailed me that his 35mm print credits Megascope, the term Hammer used for the films it shot in Super 35 and Columbia used on spherical films it released in Europe with anamorphic prints.

RICK: Incidentally, re your Lippert Pictures filmography, THE BIG CHASE was expanded from what was to be 3-D short, I believe BANDIT ISLAND.

KIT: True; producer Robert L. Lippert, Jr. made both the 3D short and incorporated the footage (in 2D) into his feature film, THE BIG CHASE (1954). The 3D short itself is not known to survive.

RICK: I believe the color films Lippert did before the formation of Associated Producers were released as official Fox films because they were in color.

KIT: The only two color films that came out of Regal Films were THE FLY (1958) and THE DEERSLAYER (1957), which were released as Fox pictures, but produced by Lippert. When the Fox-Regal deal expired, a new one was set up under the name Associated Producers. Many of those were in color.

RICK: Were CATTLE EMPIRE, VILLA! (both1958) and THE OREGON TRAIL (1959) not part of the Lippert deal? They are credited as being produced by Richard Einfield, the son of a former Fox exhibition executive. I’d gotten the impression that all the obvious color B’s Fox released during the Skouras years went through the Lippert Unit. [condensed for clarity]

KIT: CATTLE EMPIRE, VILLA! And THE OREGON TRAIL are Lippert (API) productions. I know IMDb isn’t the be-all-end-all of credits, but it doesn’t list CATTLE EMPIRE or VILLA! as Einfield films. Maury thinks Einfield “may” have produced CATTLE EMPIRE, and he did produce OREGON TRAIL.

Both Dexter, and VILLA! star, Margia Dean, confirm that Spyros Skouras’ son, Plato Skouras, produced VILLA! Dexter says that Plato wanted to be a movie producer so his father assigned him to “produce” some Lippert’s, a way to get him off his back and still allow his son to call himself a producer, although his involvement usually wasn’t much more than as a figurehead. Dexter adds it was a similar situation with Richard Einfield, whose father was indeed an exhibitor, and therefore a customer of Fox. He added that Einfield did not have much to do with the actual producing, but did more so than Plato Skouras given Einfield had a background in film editing and directing.

Dexter has given me more details on THE FLY. He says Lippert read the “The Fly” short story in a 1957 Playboy Magazine, at the suggestion of director Kurt Neumann. He immediately dispatched someone to Paris to buy the movie rights from its author, George Langelaan. Langelaan was paid $2,500, a little over $19,000 in 2010 dollars.

I’m thankful for Rick’s questions and comments, and hope he will contribute more.

GREAT NEWS! Maury Dexter wrote an unpublished autobiography which I found to be a page-turner. He has asked me to make it available at no charge. I’ll get to work on the project as soon as I can figure out how to upload the book from a floppy disc!

Recommendations:

Google Rick Mitchell, or start with this site:

http://www.in70mm.com/workshop/departments/mitchell/index.htm

Visit our website to order DVDs from the Kit Parker Films Collection –

Keep up to date with our new Sprocket Vault releases by liking us on Facebook www.facebook.com/sprocketvault/

Also, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel:

Please bear with me while I get over my passion for compiling lists!

I’ve spent weeks putting together a filmography pictures produced by various companies controlled by Robert L. Lippert. So far there are over 300 (!) productions spanning a 20 year period commencing in 1945. It’s been interesting, fun, and definitely time-consuming! My goal is to make this information definitive…not an easy task given many of the movies were made anonymously. Look for it soon. In the meantime I offer you the lists below.

Lippert Pictures: Unrealized Or Retitled Projects

During 1947-49, Lippert Pictures, and its predecessor, Screen Guild Productions, announced titles to trade publications become available in the “next season,” implying they were in production, or close to it, or “in preparation,” which was another way of saying little, if anything had been prepared other than the main title.

During my interviews with producers Maury Dexter and Robert L. Lippert, Jr., I was told by both that Lippert, Sr., almost always came up with a title before commissioning the screenplay, but did occasionally change his mind, ending up releasing the picture under another title. For example, the announced title, “The Ghost of Jesse James,” could have been changed to “The Return of Jesse James,” which actually was released. At this point we’ll never know which titles were abandoned, or actually released under other titles.

I’ve always wondering what a Lippert production of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, much less directed by Samuel Fuller, in CineColor, or a Wizard of Oz sequel would have looked like had Lippert Pictures actually produced them!

Titles announced as being available “next season”

20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA – Project sold to Walt Disney

ABILENE KID, THE

ALGIER’S AMBUSH – George Raft

ALOHA

BLACK TULIP

COME OUT FIGHTING

CORNY RHYTHM

CROSS-CURRENTS

DEAD END CANYON

DEAD RINGER

DESERT QUEEN

FOR DISHONOR

FORT DEFIANCE

GHOST OF JESSE JAMES

GREAT JEWEL ROBBERY, THE

ISLE OF ZORDA

KING OF THE SAFECRACKERS

MADAM SHERIFF

MONTANABADLANDS

MUSTANG FURY

PARK ROW *

PILLAR MOUNTAIN

SON OF SHEP

STRATOCRUISER

WOMAN WITH A GUN – Paulette Goddard

* Samuel Fuller eventually produced in 1951 for U.A. release

Titles announced as being “In Preparation”

CABOOSE

FIREBUG AGENT

HIGHWAY WESTWARD

REDSKIN RENEGADES

STREAMLINER LIMITED

Titles unrealized

BANDOLEER

CALIBRE .45

DALTON’S LAST RAID, THE

DAREDEVILS OF THE HIGHWAY

I WAS KING OF THE SAFECRACKERS

OUTLAW HIDEOUT

RADIO PATROL

STRANGER IN THE HOUSE

SUNSET RIM

TALES OF CAPT. KIDD

ABILENE KID, THE

WESTERN BARN DANCE

WESTERN FURY

WIZARD OF OZ, THE – Series

————————

Visit our website to order DVDs from the Kit Parker Films Collection –

Keep up to date with our new Sprocket Vault releases by liking us on Facebook www.facebook.com/sprocketvault/

Also, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel:

“’The Black Pirates’ (1954) was shit, and ‘Massacre’ was no good either.” — Producer, Robert L. Lippert, Jr.

By 1959 the Lippert/Fox/Regal Films contract was finished. However, Fox still needed B movies, and Lippert was always the man for that job. A new 7-year deal was struck.

The new production entity became known as “Associated Producers, Inc.” (API). Bill Magginetti continued running the company and, of course, Bob Lippert called the shots. When the API deal ended, “Lippert Pictures” was reactivated and produced another 10 films for Fox release.

Producer/director Maury Dexter was a pivotal figure during the Lippert-Fox years. Dexter told me he was born into poverty during Depression-era Arkansas. He became interested in acting, came to Los Angeles, and had a few bit parts in films, including the 3 Stooges short “Uncivil War Birds (1946), and became involved in TV and stage. He served in Korea, and soon after was hired by Regal Films head of production, Bill Magginetti, as his assistant. When Lippert fired Magginetti, Dexter took over. It was a good decision as Dexter was a natural organizer, could do many things at the same time, quickly and under pressure…the prerequisites for success at Lippert! In addition to overseeing the company, he personally produced and directed 16 feature films!

After almost two decades in production, Robert L. Lippert returned to Alameda where he died of a heart attack at the age of 67 on November 16, 1976 in Alameda, California.

Lippert Trivia:

Samuel Fuller was set to write and direct a Lippert production of “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea,” in CineColor as announced in exhibitor publications in 1949. Walt Disney bought the project from Lippert Pictures, either because it inspired him to make his own version, which he eventually did 5 years later, or he had planned making it all along and didn’t want another version to compete against.

Robert L. Lippert entered into negotiations with the Estate of author L. Frank Baum for rights to produce a series of “Wizard of Oz” movies. The reason he abandoned the project is lost to history.

The shortest shooting schedule of any Lippert production was one day, “Hollywood Varieties” (1950).

The runner up at 58 hours is “Highway 13” (1948). Coincidentally, it was a 58 minute movie, so it literally took only one hour to produce one minute of screen time!

Lippert productions had a minimum of 50 daily camera set-ups.

Just to prove he could do it, producer Robert L. Lippert decided to direct a movie, “The Last of the Wild Horses” (1948.) When production fell behind he fired himself and Paul Landres completed the film. After that Lippert stuck to producing. BTW, Lippert accorded himself something he never allowed other directors…an extravagant (for a Lippert production) running time of 84 minutes.

After a day of filming “Massacre” (1956) in Guatemala Producer Robert L. Lippert, Jr. was relaxing in his hotel room and heard gun shots in the room next to him. Recalling that a General was staying there, he immediately calculated it was an assassination (it was.) Lippert didn’t want to be shot as an eye witness, so he jumped out the window and ran on foot all the way to Mexico, and the cast and crew, who were staying in another hotel, departed by plane.

Again during the filming of “Massacre,” Lippert, Jr. said he was on location in a rural town where he found the electrical power was at best unreliable. Of course power was essential. To proceed with filming he went to the local airport, such as it was, which was powered by a generator. He paid off government officials to obtain the airport generator during the daytime hours. Daytime air operations ceased, and each night the generator was returned to the airport thus enabling planes to once again take off and land.

There wasn’t enough money in the production budget to afford a pirate ship in “The Black Pirates” (1954), so the movie begins with the “pirates” arriving on shore in a row boat. They never leave land for the entire movie.

Beloved character actor, Sid Melton, made 20 appearances in the early Lippert productions before becoming a TV mainstay. I asked him why he was in so many, and he replied, “Mr. Lippert had faith in me.” The fact Melton was willing to work for $140 a week may have helped. (2)

Between 1955 and 1965, Lippert co-financed and/or co-produced four European productions not released by Fox: “The Quartermass Xperiment” U.S. title, “The Creeping Unknown” (U.K./1955), a Hammer Films production released through United Artists; “The Last Man on Earth” (Italy/1964), filmed in Rome and released by American International Pictures; “Walk a Tightrope” (U.K./1965), released through Paramount; and “The Woman Who Wouldn’t Die” (U.K./1965), released through Warner Bros.

Margia Dean, Actress and Producer

Several years ago I met Margia Dean, still charming and beautiful, who appeared in 39 Lippert productions.

She revealed a story about Clint Eastwood who appeared with her in “Ambush at Cimarron Pass” (1958). Years later at a Hollywood function, she ran into the by-then renowned actor-director and couldn’t resist chiding him, “Just remember, I got top billing over you!”

Here are some more fun bits she told me on June 17, 2011: “I was executive producer of ‘The Long Rope’ [1961] starring Hugh Marlowe. That was the only one for Fox. I was associate producer on a couple of others. It came in on time and made money. I remember that I had difficulty getting respect because I was a woman [producer] and that was very rare in those days.”

“There was a scene in a little Mexican town and it was too bare, so I suggested that they have a few chickens and a stray dog for some atmosphere. Someone said “the producer wants chickens” and when I came on the set it was swarming with chickens! The writer [Robert Hamner] told me I was the best producer he ever worked for and he worked for several big producers. I remember one was Aaron Spelling.”

I remember that the star wanted some aspirin so I asked the driver to go to the drug store and get some and he replied that according to the union he couldn’t go, he could only drive, so I went along, and got the aspirin. Then, in a cantina scene I asked the prop man to put some serapes on the wall and he said he couldn’t, I would have to hire a drapery man, so I hung them! I hired the director [for “The Long Rope”, William Witney] whom I worked for in another film (Secret of the Purple Reef) [1960] and I sensed he didn’t like taking any suggestions from me!”

* Mr. Lippert did produce, direct and or edit some good films!

The Robert L. Lippert Foundation. Good overview with biography and filmography, the latter of which I am in the process of revising.

http://robertllippertfoundation.com

Maury Dexter interviewed by Tom Weaver in “I Talked With a Zombie”

http://www.mcfarlandpub.com/book-2.php?id=978-0-7864-4118-1

Sid Melton:

http://www.bmonster.com/profile38.html

Sources: Conversations between Kit Parker and Robert L. Lippert, Jr., Maury Dexter, Margia Dean and Sid Melton; issues of Motion Picture Herald and Film Daily Yearbook; the Kit Parker-Lippert Collection at the Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; interviews with Maury Dexter and Sid Melton by Tom Weaver in “I Talked With a Zombie” (BearManor Media, 2011).

——————–

Visit our website to order DVDs from the Kit Parker Films Collection –

Keep up to date with our new Sprocket Vault releases by liking us on Facebook www.facebook.com/sprocketvault/

Also, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel:

“That Thanksgiving we had two turkeys”

The early days of television were a boon to independent producers like Lippert because they could now license their movies to television. The big studios could too, but were afraid to alienate exhibitors they were dependant on to show their new releases. Although Lippert had problems with exhibitors as well, his first major hurdle were the music composer and musician unions. He had previously paid them when his movies were first made. He had the right to show them anywhere, but the unions wanted additional compensation for TV, and threatened television stations if they dared to air them. At first he replaced the original compositions with monophonic organ scores. Eventually the original music was restored, but his problems were just beginning.

The Screen Actor’s Guild (SAG) told him that unless he gave their members residuals for television airings, he couldn’t use SAG actors in future productions. Lippert’s position was the same, but he couldn’t make movies without actors, so he closed “Lippert Pictures.”

Lippert still wanted to produce movies, and 20th Century-Fox needed to get out from an edict it handed down to exhibitors.

The Fox problem began after it notified exhibitors that all of their forthcoming productions would be in color, CinemaScope, and stereophonic sound. But Fox still needed “B” movies as second features to its “A” product. Also, drive-ins were coupling two B’s together as double features. In any case, Fox couldn’t afford to make them in color.

Lippert and Fox head, Spyros Skouras, came together and created Regal Films, solving both of their problems with one name change. Ed Baumgarten, former chief loan officer for the motion picture division of the Bank of America, and Vice-President of Lippert Pictures, became the straw man “president” of the company. Lippert called all the shots, but with his name appearing nowhere in the credits, he was free to sell his movies without fear of union reprisal.

Concurrently, Fox got out of its ill-conceived “color, CinemaScope, stereo sound only” policy by informing exhibitors that the Regal films were independent productions, merely distributed” by Fox…technically true, even though Fox provided the funding.

All of the releases* were black and white and “RegalScope,” which allowed Fox to keep its prestigious “CinemaScope” name off low budget, black and white movies. Earle Lyon, producer of three Regal films, told me that RegalScope was strictly a name change, and that the lenses used in the RegalScope productions were the same CinemaScope ones used for the regular Fox “A” titles.

Maury Dexter, who started out as Lippert’s assistant in 1956, and later became one of Lippert’s most prolific director and/or producers during the Lippert-Fox era, told me the budgets were only $100,000 (just under $800,000 in 2010 dollars), which is incredibly low considering the production values, such as they were. I’m told Lippert got an additional $25,000 as a producer’s fee. “The Fly,” which was in color, cost $700,00 – $750,000 (Approx. $5.5 million in 2010 dollars) according to Maury Dexter who was in charge of production at Lippert.

The only Regal color productions were “The Deerslayer” (1957), and “The Fly” (1958), which along with Samuel Fuller’s black and white, “China Gate” (1957), were released under the Fox/CinemaScope banner. When I used to distribute those pictures through Kit Parker Films, there was an occasional instance where one print had a Regal logo, and another a 20th Century-Fox one…I have no idea why.

I asked former exhibitor Shan Sayles, if he played any RegalScope movies. He told me “Yes, a western double feature that ran on Thanksgiving of 1957,” continuing, “that Thanksgiving we had two turkeys!”

One of the unfortunate hallmarks of many of the Regal titles is too much talk, too little action. According to his son, Robert L. Lippert, Jr., the elder Lippert knew it was cheaper to film dialogue than action.

Producer Earle Lyon told mes a story about Lippert’s penuriousness while in Montana producing “Stagecoach to Fury” (1956), Lippert’s only Oscar nominee – for best black and white cinematography, when he got a call from the boss asking him to get to Las Vegas right away for an urgent meeting. The “meeting,” according to Lyon, lasted about three minutes, long enough for Lippert to tell Lyon the movie was not to go one cent over budget. “Do you understand, not one cent. Now go back and go to work!” Why Lippert spent money on a plane ticket to tell Lyon something that he and everyone else knew was an iron-clad rule, remains a mystery!

In 1959 Regal Films was abandoned altogether, but Lippert continued to produce low budget movies for Fox for another ten years. It puzzles me that Fox didn’t release those films to television. Instead, Lippert somehow gained control of the Regal library, and in the early 1960s sold them outright to National Telefilm Associates (NTA.) Paramount is the current owner.

But there’s more to Lippert’s producing career…to be continued…

* At the time of the Regal deal Lippert had one unreleased picture, “Massacre” (1956), a USA-Mexico co-production Lippert and Intercontinental Pictures, Inc. Fox’s involvement was only as distributor.

(References: Robert L. Lippert, Jr., Maury Dexter, Earle Lyon and Sam Sherman)

————————

Visit our website to order DVDs from the Kit Parker Films Collection –

Keep up to date with our new Sprocket Vault releases by liking us on Facebook www.facebook.com/sprocketvault/

Also, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCLHjjG-o5Ny5BDykgVBzdrQ